Recently I attended the Global Health Lecture Series at the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, and one lecture by Professor Adam Kucharski left a strong impression on me, the topic being How certain is certain enough? Professor Kucharski is an expert in the study of uncertainty, and the lecture was relatively popular science in nature, primarily intended to explain to the public the meanings of probability, statistics and certainty. During the lecture I suddenly realised that value-investing decisions can be understood from the perspective of social epidemiological decision making, especially the confusion matrix (Confusion Matrix). I therefore decided to record these thoughts and hope that everyone can join the discussion 🙂

“In the kind of work we engage in, the degree of certainty required in experiments is not an abstract mathematical demand, but must depend on the economic benefits that can be obtained from acting on the experimental results; only by weighing the potential returns against the cost of the experiment can one determine what degree of confidence ought to be achieved.” ——William S. Gosset (pen name “Student”, inventor of the Student T distribution and the Student T test), internal memorandum to the Guinness Brewery, circa 1904–1905

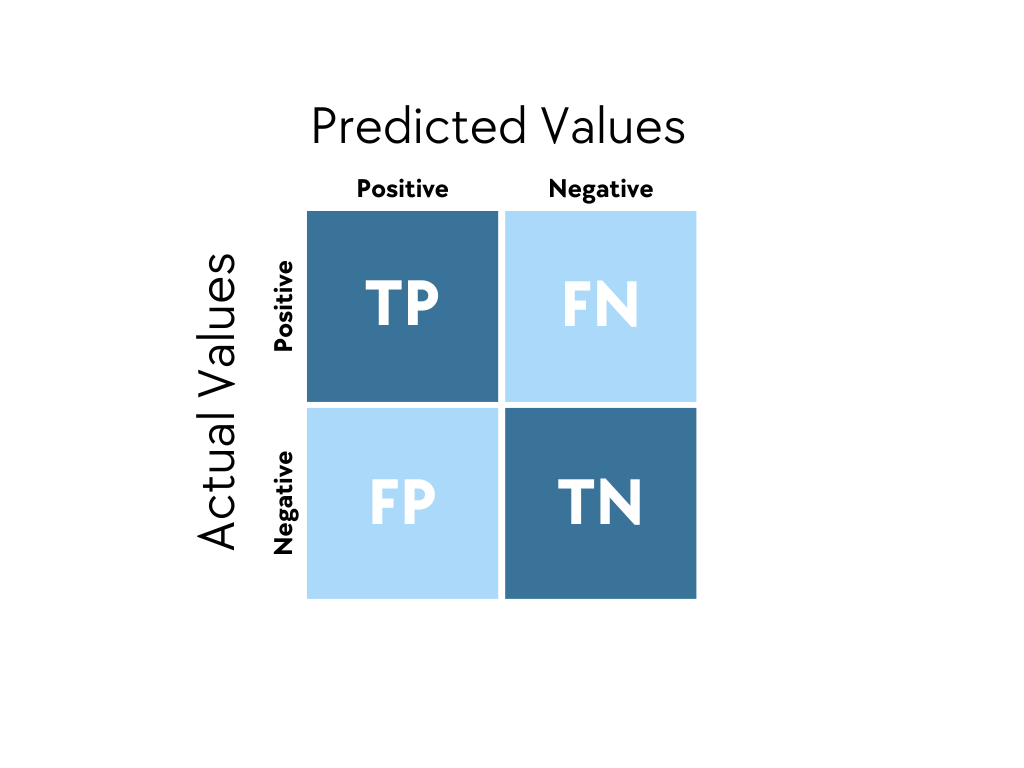

Confusion Matrix

What is a confusion matrix? It is a tool used to evaluate the performance of classification models by comparing predicted results with actual outcomes, showing four possible situations: True Positive (TP), False Positive (FP), True Negative (TN) and False Negative (FN).

In epidemiology, confusion matrices are widely used in the evaluation of disease screening and diagnostic tests. Take COVID testing as an example: a true positive indicates that the test correctly identifies an infected person, a false positive indicates that an uninfected person is misclassified as infected, a true negative indicates correct identification of an uninfected person, and a false negative indicates that an infected person is misclassified as uninfected. By analysing these four indicators, public health decision makers can compute sensitivity and specificity, evaluate the accuracy of testing methods, and make more informed decisions on disease transmission risk, allocation of medical resources and isolation policies. False negatives may allow infected individuals to remain unisolated and continue to spread the disease, while false positives may cause unnecessary panic and waste resources, therefore understanding and optimising the confusion matrix is crucial. In practical application, decision makers need to choose appropriate evaluation metrics according to the specific scenario and decision objective. Different scenarios have very different tolerances for false positives and false negatives, which directly affects which metrics we should prioritise. For example, in early cancer screening the cost of false negatives is extremely high, missed diagnoses may cause patients to miss the optimal treatment window and even endanger life. Therefore sensitivity should be prioritised (Sensitivity = TP / (TP + FN)), to ensure that as many potential patients as possible are identified. To achieve this goal we can accept a relatively high false positive rate, because the cost of follow-up examinations is far lower than the consequences of missed diagnoses. The decision principle in this case is “better to kill a thousand wrongly than to let one go”, even if some healthy people are wrongly told they need further tests, the inconvenience and anxiety are far smaller than the risk of missing a cancer patient. By contrast, rare disease screening requires different trade-offs. When disease prevalence is extremely low (for example one in a thousand), even if sensitivity and specificity are both high, there may appear the counterintuitive outcome that “most positive results are false positives”. This is because under low prevalence, even a low false positive rate can produce an absolute number of false positives that far exceeds true positives due to the large base of healthy individuals. For example, suppose disease prevalence is 0.1% and sensitivity and specificity are both 99%. In a population of 100,000 there are 100 true patients, of whom 99 will be detected (TP = 99); among 99,900 healthy people, 999 will be misdiagnosed (FP = 999). This means that among 1,098 positive results, only 99 are true positives, the positive predictive value is only about 9%. Therefore in rare disease screening we need to pay special attention to positive predictive value (PPV = TP / (TP + FP)) and negative predictive value (NPV), rather than sensitivity and specificity alone. In practice positive results usually need confirmation by more precise confirmatory tests to avoid overdiagnosis and the financial, physical and psychological burdens that follow.

Overall, there is no universally optimal metric in epidemiological screening, the best metric depends on the specific application and decision objective. In complex situations it is often necessary to consider multiple metrics or to design multi-stage decision processes to balance different needs. Understanding the essence of the confusion matrix is not just mastering a statistical tool, it is acquiring a systematic framework for risk decision analysis. This ability applies not only to epidemiology but also to the value-investing decision field that we will discuss next.

The Pursuit in Value Investing

Given the classification of uncertainty provided by the confusion matrix, what should value-investing decisions pursue? My personal understanding is that value investors should pursue high precision (high true positive, Precision = TP / (TP + FP)). Specifically, value investors should pursue high TP (correctly identify and invest in high-quality targets), strive to reduce FP (avoid investing erroneously in non-high-quality targets), while the corresponding FN (missed investment opportunities) size is not actually very important. The conservative philosophy of value investing essentially prioritises the quality of investment decisions over quantity, which is the opposite of the cancer screening strategy that pursues high sensitivity (minimising missed diagnoses). As value investing masters such as Buffett or Sir Chris Hohn repeatedly emphasise, value investors need to concentrate on holding outstanding companies for the long term, and missing some companies (FOMO) is relatively unimportant. As Buffett said, “The first rule of investment is not to lose money, the second rule is not to forget the first rule.” This perfectly explains why value investors should prioritise precision rather than sensitivity. Buffett did indeed miss many investment opportunities (high FN), for example he admitted missing tech stocks such as Google and Amazon. But this strategy helped him avoid many investment errors (low FP), ensuring Berkshire Hathaway’s portfolio remains high quality. As Buffett said, “You do not need to do many things right, you only need to avoid big mistakes.” Once we clarify what we pursue in value investing, we can largely know what information to gather and how to decide.

Decision Making in Value Investing

First, a common way to improve precision is to raise the threshold (threshold). In classification models the threshold determines the criterion for labelling a prediction as “positive”. Raising the threshold means only predictions the model is more confident about are classified as positive. This produces two key effects: firstly, reducing false positives (FP), stricter standards filter out predictions the model is less certain about, thus reducing erroneous positive judgements; secondly, retaining high-confidence true positives (TP), those cases the model is very confident about will still be identified. Since precision is calculated as Precision = TP / (TP + FP), when FP in the denominator decreases significantly while TP in the numerator remains relatively high, overall precision improves. In value investing, raising the threshold manifests as setting a margin of safety. Margin of Safety is a foundational concept of value investing introduced by Benjamin Graham and popularised by Buffett. One only invests when the stock price is well below intrinsic value, that gap being the “margin of safety”. From the confusion matrix perspective, setting a margin of safety is equivalent to raising the investment decision threshold, only those with significant discounts and outstanding quality pass the filter. Although setting a margin of safety may cause value investors to miss some opportunities (increasing FN), it ensures higher quality of actual investments, reduces erroneous investments (lower FP) and thus increases precision. Philosophically this can be understood as adopting an epistemic “sceptical confirmation logic” in the process of classifying the world. That is, we do not change the evidence itself, but change the norm of “what evidence suffices for an affirmative judgement”, so that when faced with ambiguity the cognitive model systematically chooses “not to confirm”, thus avoiding declaring a false fact as true. Its essence is the “high-cost confirmation rule” in decision philosophy. When confirming a proposition as true entails very high risk, the rational strategy is not to search for more true cases but to raise dramatically the threshold for acceptance to minimise erroneous affirmative judgements. Therefore this method does not make the model “know the truth better”, but makes the model adopt stricter, more conservative norms about “when to admit something as true”, thereby structurally compressing false positives.

Second, another way to improve precision is class undersampling in machine learning, more specifically positive-class undersampling. In the standard literature this usually belongs to Imbalanced Learning strategies, but unlike the usual purpose this strategy is not to make the model better at recognising the minority class, rather it aims to shrink the decision boundary of the minority (positive) class to reduce false positives (FP) and thereby increase precision. In common scenarios this strategy is rarely adopted because it harms recognition of the positive class (increases false negatives), but under value investing’s explicit objective structure of “not caring about FN, only caring about FP” it becomes logically, mathematically and philosophically reasonable. From the perspectives of epidemiology and machine learning, the mindset of value investors can be understood as an epistemic strategy of actively contracting the positive class. Value investing does not try to identify all potential future winners, but by constructing extremely strict judgment standards actively narrows the boundary of the “good company” category: only companies with solid business models, excellent capital allocation, trustworthy management, mature culture and a margin of safety are allowed into the candidate set. This process very much resembles the effect of positive-class undersampling in machine learning, where the model only admits the most typical, clearest samples into the positive class and excludes all borderline, ambiguous or insufficiently evidenced samples. The result is a marked reduction in false positives (investment mistakes), thereby improving investment judgement precision; as for missing some good companies (false negatives), although their number may rise, the long-term cost is far less than a single major erroneous investment. In other words, the essence of value investing is not to expand the possibility space, but to raise the confirmation threshold, forming a sceptical confirmation logic: rather than being over-optimistic, be cautious in affirming. Further, the long-standing investor maxim “less is more” is not mere intuition but a profound probability structure. When the cost of erroneous affirmative judgements (false positives) far exceeds the cost of missed opportunities (false negatives), the optimal strategy is not to try to catch more potential winners but to actively shrink the definition space of the positive class. The investment systems adhered to by Buffett, Munger, Terry Smith, Chris Hohn and even James Anderson are essentially a structural contraction of the positive class. Value investors do not seek all excellent companies, they deliberately compress the candidate set and only bet on the most exceptional, most durable, most certain companies within their circle of competence. By defining strict boundaries they systematically reduce the probability of major mistakes, so the investment process focuses on “avoiding big mistakes” rather than “pursuing complete victory”. This is not a stylistic preference but a deep decision philosophy aligned with uncertainty and cost structures.

Another common method to improve precision is improving negative-class feature quality. Simply put, under this strategy the fundamental way to reduce false positives is not to make the model “understand positives better”, but to make the model “understand negatives better”. In epidemiology negative samples are often numerous and internally complex, and if the model cannot fully grasp “what the normal pattern of healthy individuals is” it will occasionally misclassify some genuinely negative samples as positive. In other words many sources of FP are not model overconfidence but insufficient cognition of negative-class heterogeneity. Therefore by enhancing negative-class feature quality, for example adding more discriminative healthy-person variables or introducing finer stratification, the model can better distinguish the boundary of normal states. Only when the “shape of the healthy” is learned clearly and richly can the model reliably identify samples that do not belong to health. From an epistemological perspective, “reducing false positives by improving negative-class cognition” embodies a reverse confirmation logic: we do not rush to confirm whether something belongs to the “good” “right” “positive” category, but instead establish more reliable boundaries by deeply understanding “what it is not”. Apophatic theology likewise holds that we cannot understand God by listing what God is, but by clarifying what God is not. This is a way of excluding erroneous paths by negative statements and progressively approaching truth by stripping away the non-true. In value investing Charlie Munger’s remark “I just want to know where I’m going to die so I won’t go there” essentially adopts the same cognitive structure. He does not try to directly predict which investments will bring enormous success (positive-class modelling) but seeks to understand deeply which situations inevitably lead to disaster (negative-class structure), thereby avoiding systematic errors. In other words he improves the quality of negative-class recognition, identifying which corporate cultures, business models, financial structures and governance modes will necessarily lead to long-term value destruction. Thus his investment boundaries become clear and robust, reducing misjudgements (FP) and increasing overall judgement precision (Precision). Understanding the true negative boundary often yields more robust decisions than seeking expansion of affirmative categories.

Removing noisy and unstable variables to tighten decision boundaries and reduce FP is also a common practice. The problem with noise variables is that they artificially expand the positive-class decision boundary, causing the model to treat some completely normal samples as “partially close to positive”, thereby generating false positives. If features are full of random fluctuations, measurement error or variables unrelated to disease mechanisms, the model cannot distinguish these noises from genuinely meaningful signals and its decision boundary becomes loose, expanded and shape-unstable. In such cases any healthy sample that by chance deviates along a noise dimension may be misclassified as positive. The effect of removing noisy features is in fact to tighten the boundary, making the positive-class dividing line clean, clear and concise. Essentially this reduces “false evidence” in the classification space so the model is no longer misled by unreliable information. Epistemologically we can view this as not increasing the model’s sensitivity to the world but cleaning up interference sources that lead to erroneous affirmative judgements; by reducing chaotic information components the model decides more cautiously and robustly who is worthy of being classified as positive. Its direct result is a systematic decline in FP. From the perspective of value investing removing noise variables to tighten model decision boundaries corresponds to investors actively filtering out random, short-term, value-irrelevant signals when evaluating companies. Noise information, whether quarterly fluctuations, market sentiment, short-term macro shocks or incidental managerial phrasing, can make investors mistakenly believe a company is “partly close to excellent” thereby expanding the universe of “potential good companies”. This closely parallels the machine learning case where noise features expand the positive-class decision boundary; when the model cannot distinguish meaningful features from random error it builds loose, expanded and shape-unstable positive regions in high-dimensional space and perfectly normal negative samples may enter, causing false positives. As Taleb said, “To make a fool bankrupt, give him information.” If investors do not proactively clean up seemingly informative noise the investment boundary loosens, wrongly treating many unworthy companies as candidates “worth a gamble”, greatly increasing the probability of erroneous investments (FP). The process of removing noise is not making investors more sensitive to the world but precisely the opposite, systematically excluding secondary clues, random fluctuations and unstructured signals that mislead judgement; it restores investment decision boundaries to being clean, clear and concise, retaining only variables truly related to long-term value. Epistemologically this is a “reduction of false evidence” strategy: by reducing chaotic information investors judge more cautiously and robustly who truly belongs to the positive class of “excellent companies”. The result is consistent: mistaken investments (FP) fall significantly while missed investments (FN) may rise slightly, but under the cost structure of value investing this trade-off is entirely reasonable.

Finally, an excessive focus on reducing false positives may create the potential problem of paralysis by analysis and large amounts of capital remaining uninvested. One way machine learning addresses this problem is by using ensemble models to filter FP, that is simulating a two-stage “screening plus review” decision procedure. In the first stage a permissive model covers all potential positive samples to ensure possible true positives are not missed (TP and FN are not critical at this stage); the second stage then uses a high-precision model specifically designed to reject FP to perform strict screening of candidates. Its structure parallels the “screening plus confirmation” process in hospitals: the screening stage tolerates false positives as long as missed diagnoses are avoided; the confirmation stage pursues high precision to ensure final positive judgements are indeed reliable. In epidemiological applications this architecture is common in airport screening, triage and infectious-disease alerts because it maintains system sensitivity while keeping final FP at very low levels. Epistemologically this strategy separates “searching for positives” and “confirming positives” into two logically distinct tasks: the former requires openness, the latter strictness, thus avoiding a performance trade-off that occurs when a single stage tries to pursue both sensitivity and precision simultaneously. From the value-investing perspective, the two-stage “screening plus review” ensemble model provides an analogous strategy. Excellent investment decisions are not made by trying in one step to “cover all possible winners” and “avoid all erroneous investments”. Instead the most robust investment systems, like clinical diagnosis, separate these two logically different tasks. In the first stage investors need a relatively permissive screening mechanism to capture all potential outstanding targets, typically by identifying industries and business models that even under great uncertainty are more likely to generate stable cash flows and monopolistic characteristics. Examples include infrastructure (airports, ports), payment systems, infrastructure-like software (such as Bloomberg) or platform companies with strong network effects, industries that naturally have higher prior probability of positives and are more likely to produce firms with genuine moats. The goal of screening is not to decide precisely which company is exceptional, but to ensure industries and structural winners that could become long-term compounding machines are not missed. The subsequent review stage undertakes the actual task of filtering false positives. At this stage investors apply extremely strict standards to judge whether an individual company truly has a sustainable moat, superior capital allocation ability, reliable governance, high-quality profit sources and a clear long-term path. That is, the review stage does not operate at the industry level but applies a very high-precision filter to candidate firms that passed the screening. Its aim is not to find more possibly good companies but to reject the vast majority of firms that are not sufficiently excellent, leaving only the handful that truly have structural advantage and sustainable excess return ability. This aligns exactly with the machine learning second-stage model designed to suppress FP: not to increase sensitivity but to ensure that each final “positive judgement” (investment decision) is extremely accurate. By separating “industry screening” and “moat confirmation” into two stages investors can remain open to potential great companies (avoid missing TP) while driving the probability of erroneous investments (FP) down to very low levels. The philosophical implication is that searching for structural opportunities is an open logic while confirming long-term value must be a strict logic; mixing the two in the same step leads to coarse judgements under uncertainty. True value investors, like effective public health systems, construct a layered system of “broad vigilance” and “strict confirmation”: permissive screening forms the opportunity set, strict confirmation forms the investment set, and high-precision long-term returns are built on systematic suppression of FP.

Some Additional Thoughts on the Learning Process

Under a similar confusion-matrix-based framework we can derive insights about which cases we should focus on in everyday learning. In machine learning data collection, if the goal is to better distinguish false positives from true positives, the key is not simply to reinforce positive cases but to systematically capture those marginal negative samples that appear to belong to the positive class but are not, while simultaneously enriching representation of the true negative structure. In other words we need not only the core features of positives but an understanding of which negatives most easily masquerade as positives, which noise signals most readily mislead the classification boundary, and which variables truly have discriminative power. The epistemic basis of such a data strategy is improving the quality of negative information and purifying the boundaries of affirmative concepts so that the model can more reliably reject erroneous affirmative judgements. The same structural insight exists in value investing: investors should study not only characteristics of great companies but also the types of firms that “look good but ultimately fail” and industries or business models that structurally cannot generate enduring moats. For example we can study Buffett’s failures such as Kraft Heinz or Bill Ackman’s failures such as Valeant Pharmaceuticals more carefully. Only when the positive-class definition is clear and the negative-class understanding is sufficient can investors’ conceptual space become clean, clear and rigid, thus avoiding mistaking pseudo-positives for true positives amid complex, noise-rich market information. Ultimately in both machine learning and value investing the key to improving precision lies in clarifying boundaries: by strengthening our understanding of “what is not” we make “what is” more reliable.

Conclusion

In summary from the confusion matrix perspective we can more clearly understand what many strategies in value investing actually mean; often at core they are ways to trade off and optimise true positives (TP) and false positives (FP) at various levels. This framework not only helps us understand the objective of each strategy but also clarifies which dimensions of uncertainty we are reducing when we implement them. Of course the main purpose of this piece is not to proclaim that “when scientists climb to the summit they find value investors already waiting there”. What I wish to emphasise is that between seemingly completely different modes of thought, whether epidemiological screening decisions, classification optimisation in machine learning or value investing, there exist deep structural similarities. This cross-domain analogical thinking not only helps us better understand the essence of certain decision problems but also gives us clearer, more systematic mental frameworks for confronting complexity and uncertainty. Ultimately regardless of the field we operate in what truly matters is understanding what kind of uncertainty we are fighting and what kind of logical structure we choose to confront it.

Leave a comment