This memo records my reflections and concerns regarding generative artificial intelligence (AI) and related infrastructure investments. Due to my limited understanding of the relevant industries, I intend this to stimulate further discussion and welcome feedback.

Currently, more market participants are beginning to question whether a bubble exists in generative AI and related investments. Such concerns are no longer limited to investors, the International Monetary Fund and the Bank of England have recently expressed similar worries, and an increasing number of media outlets have drawn comparisons between the current investment frenzy and the internet bubble of the early 2000s. In contrast, tech giants led by OpenAI believe the market is not overheated. In the short term, buoyed by relatively optimistic market sentiment and OpenAI’s significant moves, stock markets continue to rise.

My perspective is comparatively pessimistic. I believe a bubble indeed exists, but its nature might differ from the commonly compared internet bubble, primarily due to differences in concentration and participant quality. During the internet bubble, irrational exuberance was reflected mainly in the IPO frenzy of numerous unprofitable internet companies. As mentioned in “A Random Walk Down Wall Street”: “During the internet bubble, the connection between profits and share prices was severed, and numerous loss-making companies flocked to the public markets.” The current situation is different: generative AI involves enormous costs and few participants, concentrated among a small number of players—major internet companies and private firms such as OpenAI, Anthropic, and xAI. Major internet firms already have mature businesses providing stable cash flows and excellent business models (such as Meta, Google, and Microsoft). This differs fundamentally from the large-scale IPOs of unprofitable startups during the internet bubble. As Howard Marks noted in his memo “Calculating Value,” current S&P 500 companies, especially leading internet companies, have significant advantages compared to dot-com-era startups and even past S&P 500 firms, featuring superior products, moats, high-margin profitability, and impressive growth potential.

My current understanding is that these companies’ cash flows can support large-scale AI infrastructure investments, making them relatively healthy in the long term. However, these investments may not be profitable and could largely be defensive, participating unwillingly in an arms race. My primary concerns regarding the AI bubble are twofold: firstly, currently unprofitable private companies, and secondly, more critically, infrastructure investments by data center operators.

Firstly, data center investment economics do not seem to add up. Allow me to quote Marathon Capital’s calculations:

Assuming data center operators require a 20% free cash flow yield to support their valuations, they would need to generate revenues of $2.5 trillion. For their customers to achieve similar profit margins, consumers and enterprises would need to spend nearly or more than $3 trillion on AI services soon. This is equivalent to 10% of current US GDP or 5% of global labor costs according to OECD data. And this only covers equipment investment costs, excluding other investments like energy infrastructure or R&D—such as Citi’s mentioned $1.4 trillion R&D expenditures or substantial signing bonuses and salaries. Compared to current AI revenues, the gap is huge. OpenAI, the company with the most daily active users, currently has an annualized revenue of around $13 billion. “The Information” forecasts this to grow to $200 billion by 2029. Citi forecasts total AI application revenue to reach around $40 billion in 2025, growing at 80% annually thereafter to $780 billion by 2030.

In sum, there is a significant imbalance between current AI infrastructure investments and potential returns, with extreme front-loading of the investment cycle far ahead of revenue realization. Bezos may see this as a healthy bubble, but I personally struggle to understand this perspective. Data centers are likely similar to photovoltaics, a highly commoditized business with little differentiation, low bargaining power, and minimal profitability. Large-scale data center construction could be a detrimental arms race, akin to aviation, where no one gains benefits. This problem is already evident, according to internal documents, Oracle’s Nvidia cloud business generated $900 million in sales over three months ending August, with a gross margin of only 14%, significantly below Oracle’s overall gross margin of around 70%. Margins will likely fall further amid intensifying competition.

More concerning than suboptimal business models is GPU depreciation. Even disregarding iterations, heavy AI workloads accelerate GPU wear, limiting their lifespan to just 1–3 years, despite typical accounting depreciation cycles of 4–5 years. Nvidia’s iteration cycle has shortened to 12–18 months, with each generation significantly outperforming its predecessor. Economically, GPU competitiveness vanishes within three years. This makes rapid payback crucial but almost impossible given current generative AI profitability levels. Companies are forced into external financing or debt cycles, clearly unsustainable in the long run.

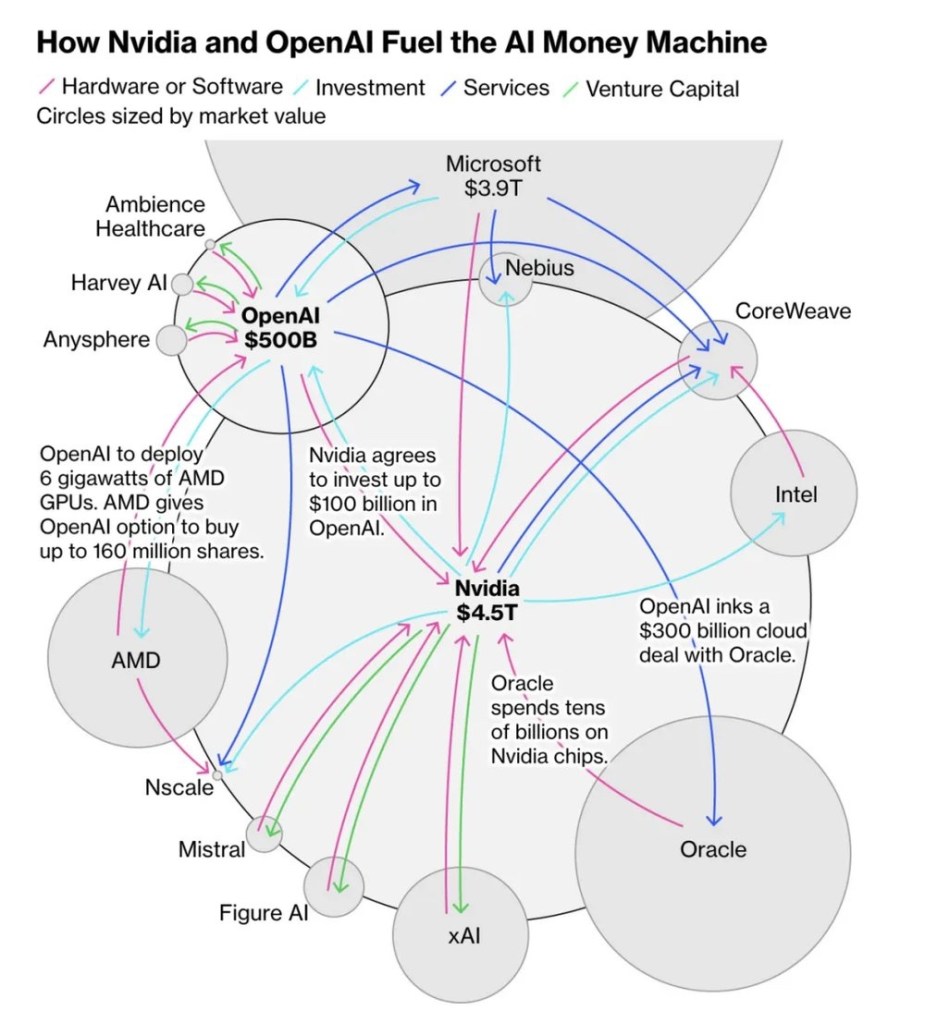

Complicating matters further, a complex capital cycle has emerged around OpenAI. Unlike listed companies with stable cash flows, OpenAI remains unprofitable. According to the Financial Times, OpenAI reported $4.3 billion in revenue in the first half of the year but an operating loss of $780 million.

As illustrated, Nvidia sells GPUs to OpenAI, Microsoft, Oracle, etc.; these companies use Nvidia’s chips to train AI models and simultaneously invest back into Nvidia or buy additional hardware. OpenAI relies on funding to purchase computing power, raise valuations, attract more investment, forming a self-reinforcing feedback loop of “capital-computing power-valuation.” Most capital flows do not stem from genuine profits or end-user demand but rather from internal reinvestments and equipment purchases, a clearly unhealthy financial ecosystem heavily dependent on external financing. A slowdown in external funding or disappointing AI revenues could quickly break this cycle, triggering valuation collapses and amplifying bubble risks.

Debt exacerbates these problems. Increasingly, companies raise substantial debts for infrastructure investments. According to Barron’s, Oracle issued $18 billion in bonds in September alone. CoreWeave, an infrastructure partner for OpenAI, also expanded its cooperation despite high financial leverage (net debt to EBITDA ratio at 5.1x). This leverage involves another less visible participant in the AI craze: private credit firms.

In simple terms, post-2008 financial crisis, tighter bank regulations restricted lending, pushing medium-sized companies towards private credit markets, which rapidly expanded. These private credit firms now finance data center construction, creating structured financing outside corporate balance sheets. This introduces around $800 billion potential investment opportunities for private credit funds. For instance, Blackstone indicated their commitment to AI infrastructure; Meta’s recent $29 billion Louisiana data center expansion was funded by PIMCO and Blue Owl Capital; Ares Management seeks over $8 billion for data centers in London, Japan, and Brazil. Due to previously mentioned over-investments, once capital inflows halt, weak profitability will render these debts risky, potentially propagating across industries via private credit.

Private credit funds magnify risks through leveraged practices such as NAV loans, potentially causing systemic risk upon AI downturns or GPU devaluations. Similar leverage practices led to concerns for Blackstone’s BREIT and other institutions amid rising interest rates. AI infrastructure finance resembles prior patterns in real estate and energy sectors, short-term high leverage supporting uncertain long-term cash flows. Systemic risks may multiply across the financial system if the cycle reverses.

Moreover, GPU collateralized financing is spreading rapidly (e.g., Lambda, CoreWeave, Fluidstack). Though superficially secure, GPUs rapidly depreciate, have volatile prices, poor secondary liquidity, and challenging resale conditions. This financing practice artificially inflates leverage and could trigger systemic risks if AI investment cools or computing demand slows, causing GPU devaluation, concentrated defaults, and potential financial contagion.

Lastly, a curious question remains regarding OpenAI’s unique structure (non-profit parent OpenAI Inc. and for-profit subsidiary OpenAI Global, LLC): how does this benefit the company amidst this frenzy?

In conclusion, I perceive significant bubble risks in current AI investments, fundamentally differing from the internet bubble. This asset-driven bubble, dominated by a few players, resembles more closely shale oil or the 1980s Japanese bubble, marked by excessive infrastructure investment ahead of uncertain and delayed returns. History shows technological revolutions often involve bubbles bursting eventually. The critical question is not if a bubble exists, but whether we are prepared for its inevitable burst.

Leave a comment