The question of what a company actually is—and why it exists—has long troubled me, and it has been an obstacle to my move into equity investing.

Ronald Coase has, of course, provided a clear explanation of why firms possess advantages over pure market exchange from the perspective of transaction costs. Yet I remain puzzled about how firms manage to survive stably over the long term, and how a company that holds substantial wealth can protect itself from predation without relying on a violent apparatus.

My confusion regarding corporate longevity arises primarily from empirical evidence. OECD statistics indicate that roughly 40%–60% of start-ups exit the market within three to five years after establishment, with minimal variation across countries. The US Small Business Administration (SBA) provides similar data: about 20% of new businesses fail within their first year, roughly 50% within five years, and approximately 70% within ten years. In other words, only around 30% of companies survive beyond a decade. German research based on Fritsch’s data estimates a median firm lifespan of approximately ten years; a Swedish study tracking companies founded in the 1990s found only 8% still operating after 14 years.

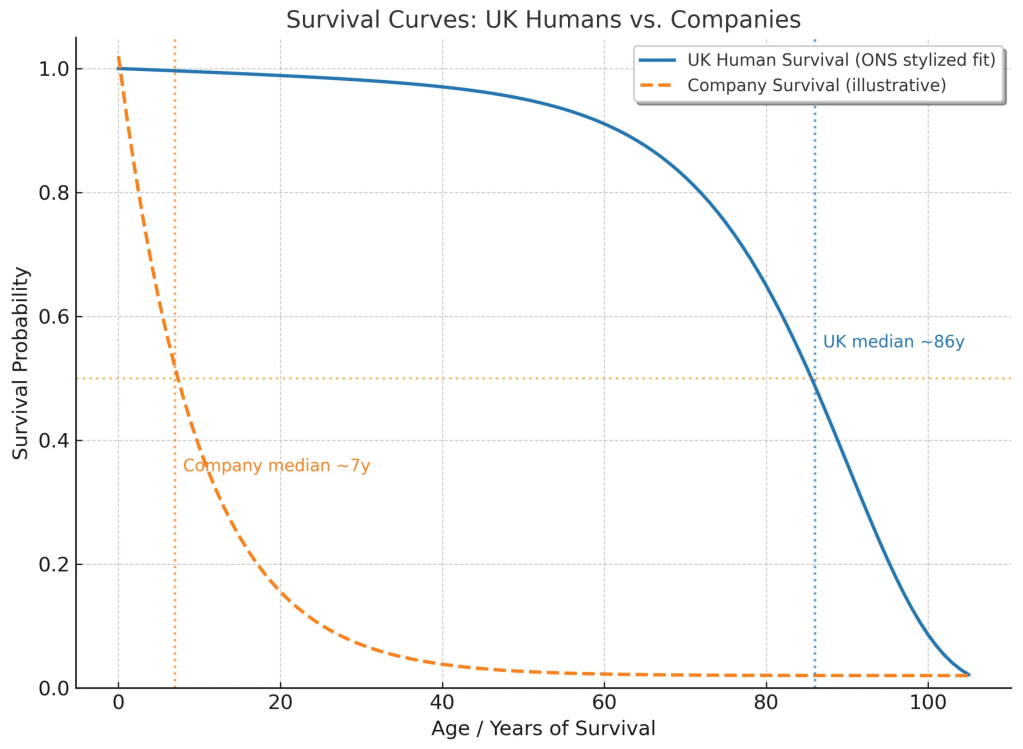

Compared with typical human survival curves in developed countries, the survival curves of companies decline far more sharply, especially in their early stages. The difference in median lifespans is stark. My first concern, therefore, is straightforward: if companies are this short-lived, does this not make lending to or investing in them exceptionally risky?

My second concern—how companies protect their wealth from predation in the absence of violence—is influenced by historical encounters involving court Jews and other financial institutions in medieval Europe. The position of court Jews was extremely precarious, relying entirely upon noble patronage. Once their noble protector died or political circumstances changed, court Jews could face exile, confiscation of their property, or even execution. A notorious example occurred in 1737: after the death of the Duke of Württemberg, his Jewish financier Joseph Süß Oppenheimer was swiftly sentenced to death. Most European monarchs viewed Jews as “property of the crown,” subject to arbitrary taxation or confiscation. When confronted by economic hardship or wartime expenditures, kings commonly resorted to seizing Jewish assets and expelling Jewish populations.

Besides the Jews, early financial institutions, such as the knightly orders, also frequently became targets of predation. Founded in the 12th century, the Knights Templar was among the earliest organisations to hold transnational properties and engage in financial activities. It possessed extensive estates, castles, and commercial assets, managed agricultural leases, conducted trade, and provided financial lending, becoming an economic entity whose wealth rivalled kingdoms. The Templars also served as fiscal agents for kings and popes, overseeing tax collection and asset management, and even holding taxation rights over local churches. Yet despite this, their wealth still became a prime target whenever royal finances became strained—Philip IV of France notably suppressed and dismantled the order. From the Templars’ example, we observe that early corporations or financial institutions, once controlling significant wealth, also exercised a degree of violence. The Teutonic Order, for instance, originated in the Crusading period and later evolved into a regional politico-military power, controlling coastal trade and urban economies. It operated mills, inns, and banking services, amassing substantial wealth from diversified sources.

As time progressed, entities resembling modern firms emerged. These early companies commanded violent resources unimaginable today. During the early capitalist period (dubbed “war capitalism” by Sven Beckert in Empire of Cotton), large enterprises such as the British East India Company and the Dutch East India Company possessed private armies instrumental to commercial expansion. The British East India Company’s forces conquered much of India through military force, notably at the Battle of Plassey, transforming the company from a commercial actor into a quasi-state apparatus. Its military, one of the strongest in the subcontinent at that time, was only dissolved by the British government following the Indian Rebellion of 1857.

By contrast, today’s largest companies hold immense wealth—around $24.9 trillion in market capitalisation and approximately $2.03 trillion in book equity—yet completely lack corresponding violent institutions. While modern business models no longer depend on violence, this raises the perplexing question: why do publicly listed companies, lacking violent protection, not fear expropriation by violent actors such as governments? This anxiety significantly hampers my enthusiasm for equity investing.

Recently, on a friend’s recommendation, I read two management classics during a holiday—Peter F. Drucker’s The Concept of the Corporation and Jim Collins and Jerry I. Porras’s Built to Last. I gradually realised that both of my concerns might be explained by a seemingly simple idea: a company is fundamentally a social organisation, and once embedded within society, it becomes difficult to remove by force.

The Concept of the Corporation provided my most significant insight by transporting me back to the early era of the modern corporation, breaking habitual assumptions, and allowing me to objectively reassess this ubiquitous entity. This estrangement clarified rather than confused, helping me deeply comprehend the firm’s nature. Widely considered the foundational work of modern management, Drucker’s book highlights management’s nascent state when firms became increasingly vital yet lacked a conceptual analytical framework. Drucker explicitly approached firms through sociological and political lenses. He wrote, “traditional sociology knew society and community, but not ‘organisation’… An organisation shares many elements with both, yet it is neither.” Earlier, in The Future of Industrial Man, Drucker asserted the need for distinct institutions in industrial societies—entities exhibiting characteristics of traditional society and community. In his view, firms served this critical institutional role, adopting functions previously carried out by families and communities. Unlike classical sociology’s emphasis on class conflict or labour relations, Drucker focused on employee–organisation relationships, individual–work relationships, and interpersonal relationships at work. This perspective was novel. From this angle, firms stand parallel to—and intersect with—other familiar social institutions such as families, social classes, schools, hospitals, and neighbourhoods. Built to Last similarly argues that founders who create enduring companies focus primarily on constructing robust organisations (“clockmakers”), rather than merely producing individual products.

Equipped with these basic concepts, we return to the original question: if most firms have such short lifespans, is investing in them excessively risky? Briefly: for mediocre companies, yes. But some firms are remarkable exceptions. Although proportionally rare, such companies exist in substantial absolute numbers. Investors must identify these exceptional, enduring firms and hold them long-term. (Incidentally, a recent study from the Oxford Institute of Population Ageing on British vehicle lifetimes found that complex machines do not necessarily follow a traditional “wear-and-tear” aging pattern. Instead, some machines exhibit non-ageing or even “reverse-ageing,” where failure rates decline with age and mileage. This finding challenges the mainstream theory that organisms inevitably deteriorate due to accumulated damage. However, there appears to be no empirical evidence yet that firms experience this “reverse-ageing” effect. See Newman, S. J. (2025). British Automobiles, Aging Theory, and the Death of Complex Machines. arXiv:2505.11505.)

As argued in Built to Last, firms that survive multiple cycles and think long-term are essentially social organisations. This insight is intuitive: families, universities, nations, and other social organisations routinely endure for centuries; it should come as no surprise that socially embedded firms might do likewise. Only when a company genuinely embeds itself as a social organisation does it become an enduring, investable entity.

My second concern—why firms without violent protection do not fear expropriation—also becomes clearer once viewed through the lens of social organisations. Simply put, violence struggles to seize deeply embedded organisations. Embeddedness manifests along two dimensions: production-side and consumption-side. Boeing exemplifies production-side embeddedness. In its Seattle days, Boeing had a renowned engineering culture; local families often included multiple generations of Boeing employees, and numerous marriages originated within the firm, similar to old Chinese state enterprises. Boeing employees reported high community prestige, proudly displaying their affiliation—evidence of profound community embedding. Notably, when Boeing merged with McDonnell Douglas and relocated its headquarters to Chicago, this social embedding severely deteriorated (an outcome some Boeing veterans blame on McDonnell Douglas’s management), eroding the engineering culture and contributing to Boeing’s recent difficulties. Procter & Gamble, discussed in Built to Last, offers another case. Its Cincinnati isolation fostered a strong corporate culture where employees socialised almost exclusively with colleagues, attended the same churches, and lived nearby. Similarly, Alibaba employees in Hangzhou proudly display company badges when purchasing property, illustrating deep social embedding.

Consumption-side embedding is equally crucial. Many enduring firms produce goods deeply integrated into daily life. Examples include dialy language use such as “I googled it”, Cheerios on many families’ breakfast tables, Warren Buffett’s beloved See’s Candies (the gift of choice for Californians), and American cultural icons Coca-Cola and Disney. Such embeddedness leads consumers to willingly pay premium prices. Firms deeply embedded either in production or consumption incur prohibitively high costs of violent expropriation. Historically, easily plundered groups lacked social embeddedness: court Jews, though wealthy, were numerically few and culturally marginalised, lacking protective social networks. Knightly orders functioned as “high-net-worth banks with mercenaries”—wealthy and somewhat armed, but lacking popular support, thus remaining vulnerable to shifting political winds.

Some may object: does a high cost of plunder genuinely deter expropriation? After all, rulers are often irrational, acting impulsively without considering long-term consequences. My practical, rather than moral, response: survival is relative. When escaping a tiger, you need not run faster than the tiger—only faster than your fellow runner.

Leave a comment